Talented cloud engineers are expensive and it's getting worse during the Great Resignation. As more and more enterprise workloads move to cloud hosting it's approaching a tipping point where this has become a serious problem. In addition to being expensive, cloud talent is very hard to find as there aren't enough people out there with the skills to satisfy the demand. Therefore, it is obvious that our current trajectory is barely sustainable and we need to figure out how to curtial the future demand and fund the current demand.

While there are many factors, one of the primary reasons for the current situation is that customized application infrastructure is pushing the engineer to app ratio closer and closer to 1:1. The need for more and more engineers combined with entry level salaries above six figures is threatening to undercut the “lower total cost of ownership” promises from cloud vendors and consultancy services. This is already affecting speed to market for applications and might even push decision makers towards cheaper, less secure options that are more expensive in the long run. Let's take at how we got here, the current challenges, and what some possible outcomes could be.

NOTE: While some of the information here is substantiated with references most of the contents are the author's opinion from working in the enterprise cloud space as an operations engineer, cloud devops engineer, operations manager, and architecture manager over the course of 5 years.

NOTE2: This is written from the perspective of a central'ish hosting organization performing cloud consulting and some high level operational support which is typical of many large organizations. What is not discussed in detail is the great range of skills that would be required of a developer embedded on an application team who has to also figure out how to build a CI/CD pipeline for the team (a.k.a, 10x DevOps Guru Person) of which there are probably only 10,000 in existence which is not enough to cover the needs of all the applications in the cloud. This elusive DevOps person's natural habitat is a startup environment and would quickly grow frustrated in a larger organization anyway.

Table of Contents

How We Got Here

It used to be that if you were a developer and you had some code you wanted to run you had to contact some central IT team and get some form of physical or virtual compute in order to run your code. This is probably via some form that asks you for your billing codes, desired cpu/ram/storage, and mother's maiden name. Then someone would get back to you in some number of weeks or months with clarifying questions and then a few more weeks/months go by and you might have a server. You'd be given an IP and SSH keys or something so you could log in and deploy your code. Whenever there was a problem with the OS/Hardware you could call some number and somebody would support you. If things got really bad you'd hear data center noises in the background of the call. In this world you could happily blame IT for all of your slowness problems and bemoan the hassle of your server going down for patching/upgrades, etc. but at the end of the day you had your domain and they had theirs. People could happily grumble their way through their work as a house divided. Life was kind of crappy but at least you could blame someone else when something went wrong.

Then came the cloud and out came the credit cards. Developers found out they could just spin up servers whenever they wanted and not be hassled by greybeards for downtime and middle managers asking them for 2 year equipment lease commitments. This was a golden era of innovation where executives one-upped each other by comparing the number of production deployments per day at the company Christmas parties and problems could be solved instantly by “cross-functional teams” with on-prem rotations. Life was good for greenfield applications.

The cloud was also starting to look attractive for legacy workloads where there were significant benefits such as cost-savings, flexibility (auto shutdown schedules anyone?), accurate inventory and billing in areas that were traditionally black-boxes. As more workloads moved to cloud, the possibility of actually closing data centers became realistic. This was the ultimate goal–no more lease agreements, no more contracts in far away places like Amsterdam, no more need for local talent and foreign labor laws, no more steak dinners and purchase order foreplay with Dell and NetApp. The on-prem exodus was in full motion. Talented data center personnel saw the writing on the wall and quietly found new jobs. Server teams and grumpy greybeards were told “there's absolutely nothing to worry about” while their budgets shrunk and their headcount froze. “Keep the lights on” posters were mailed out to every location.

There was also a new lifeline for those forward thinking, talented infrastructure architects coming from the legacy space and devs with an interest in infrastructure because now they had Legos to play with and they could build literally anything they wanted via clicks/API's. When a product owner approaches them wringing their hands with an infrastructure problem looking for a solution it's now a pleasure to solve and become an instant hero at the same time. Instead of an exercise in monotony and a bloated solution involving racks of hardware it's now a puzzle to find out how to solve their problem in the most clever way possible using the most non-standard solutions (as a bonus, now they can put “serverless” on their CV and get a new job with free snacks). A bespoke solution at the lowest cost to solve exactly the right problem is a win-win for everyone, right?

However, some interesting things started happening in cloud land like S3 data breaches, entire teams leaving the company and leaving 900 EC2 instances running some unknown critical application, promises of massive savings through enterprise agreements and reserved instance purchases, and connections to the corporate network through DirectConnect/ExpressRoute. The borders were now threatened, entire towns were in need of federal aid, tax revenue was being lost and the Federal Marshals had to restore order to the Wild West. The great centralization effort began and it was time for Corporate to lay down the law.

No longer was it OK to have warrant less public S3 buckets, wide open security groups, marketplace OS images from “hackme.ru”, and credit cards funding accounts. There was a need for master payer agreements, governance policies, and account creation departments. This was generally agreed to be a good thing and a lot of the best cloud talent from the Wild West was hired into the central teams. The free love of the 60's had ended and now it was Reagan's War on Drugs. The cloud was still pretty flexible but there are some pretty serious controls in place. “Cowboys” were devalued and while some talent in the remote offices still saw the need to stick around and keep building infrastructure for their developers, a lot of them left to go someplace with more freedom–likely someplace earlier on in their cocaine infused cloud craze and cowboy salaries.

This leaves us with some pretty talented central teams and a lot of disenfranchised sub-departments. The idea is now that these central teams have “control” can help the departments out with all of their cloud needs which seems reasonable as everything can be done in a browser and there's full visibility into all departments. Flexibility, however, can be a cruel mistress. Now we enter the modern age.

The Current Challenges

cloud person[ kloud pur-suhn ]

noun, plural cloud people

- a human being who is incapable of hosting an application on EC2 and insists on using serverless because they're religious beliefs do not allow them to deploy a sub-optimal solution

Now we find ourselves with full control over a few hundred AWS accounts with a few thousand variations of infrastructure patterns. How do we maintain control while also fostering a culture of innovation? There are multiple approaches that are outside the scope of this discussion but no matter how you solve it you end up in one of the following situations:

- A large central team of cloud people with full control with a minority of application-aware sub-department cloud people with no power.

- A small central team with full control and a large number of application-aware sub-department cloud people with some power.

In either case your cloud people are going to have to get good at managing applications. After all, that's the whole point of cloud is to host some code that adds some sort of business value, right? This wouldn't be too much of a problem if everything looked the same–if it was all just boring EC2 instances with a sprinkling of RDS. However, while the people came for EC2, they stayed for lambda and life is complicated now.

Now there's a new predicament: you need smart people to manage the complexity of the platform and the application. It's almost impossible to divorce a cloud-native application from the underlying infrastructure but since all the power has (justifiably) been taken away from the cowboys, your new cloud people (the ones wearing collared shirts) have to get to know the applications intimately. This means the cloud person to application ratio is anywhere between 3:1 and 30:1 depending on a salary between $80k/yr and $200k/yr. Without some form of standardization, this leaves your per-application infrastructure talent cost somewhere between $7k and $26k. For an organization with 200 applications that's between $1.4 million/yr and $5.2 million/yr outside of your expected cloud bill, developer salaries, and administrative salaries. That's a pretty sobering number to be looking at after someone told you Cloud could solve all your problems.

Of course, these numbers can be reduced via standardization but have you ever tried telling an application team they can't use anything except EC2? What the hell is the point of cloud if I can't use Cognito and ML!? What is the real cost-savings if all you're letting people use are things from the compute portfolio? And let's say you do manage to set an “EC2 Only” policy. Who is going to go out to an application team and tell them they have to go back in time to 2010 during their next outage window? What cloud-person (aka smart person) would tolerate being hamstrung with no chance of fluffing up their CV?

Even if you wanted to make a massive central department of cloud rockstars you're now trying to pull that talent in from the free market where they've been getting cowboy salaries for the past five years. How do you even pull cowboy talent into a role where they have to manage the infrastructure for thirty different applications? How do you fund their roles?

In many ways cloud people have brought this problem on themselves. When people came to them looking for solutions they were so enamored by the possibility of building the best solution with their new shiny tools that they failed to play the tape forward and think to themselves “How am I going to manage 200 applications with 130 different architectures?".

One is reminded of the history of automobile where in the beginning, every car was a custom job commissioned through a carriage works. There were hundreds of firms claiming they could build the best automobile and it was a golden era of innovation and creativity. However, the costs were high and the first automobiles were only available to the wealthy. Repairs and modifications could only be done by the manufacturer in many cases. Henry Ford saw the inefficiencies in this model and is famously credited for bringing the automobile to the masses via standardization. The first mass produced automobiles had almost no custom options from the factory which was advertised almost as a feature in the quote “Any customer can have a car painted any colour that he wants so long as it is black” ref. This model was obviously wildly successful and over time, manufacturers became bigger and bigger via acquisition and mergers until hardly anybody could tell the difference between a Civic and a Corolla. Exciting vehicles became a fringe movement.

To shelve the analogy, the corporate cloud is in a phase where everything is still a custom job and Henry Ford hasn't come along yet. Cloud infrastructure is still pretty expensive because despite the Lego pieces being standard they are often put together in completely unique configurations. There is very little standard work which leads to a management conundrum and soaring costs. But what are our options?

Possible Outcomes

There are a few directions to go from here which all have their pros and cons: keep building custom solutions and just pay more people well or standardize the work and make IT boring again. But before we go through these two scenarios and flesh them out a bit let's define what we see as the primary responsibilities of a centralized cloud management team.

- EVM (aka, patching) - vulnerabilities must be patched frequently and if the central teams think the application teams will do this then they're just wrong–nobody patches if things are working. This becomes tricky with serverless and especially with docker images. Can you imagine forcibly changing someone's Dockerfile from

FROM ubuntu:18.04toFROM ubuntu:20.04and expect everything to work? These things are just hard and take smart people to solve. - Audits - if you're going to be hosting any workload for a large organization then likely you'll be hosting SOX/PCI/HIPAA applications in which case auditors are a fact of life–like termites and the common cold. Often times app teams are the primary target for these auditors but they'll very quickly commission the cloud team for assitance. They're just going to come and wreck you at the worst possible time. They'll come out of nowhere one day and say something like “You are hereby ordered to make sure every Security Group in these three accounts has the ‘all outbound traffic’ rule removed”. This is a serious technical challenge that requires very smart people to solve at scale and a deep knowledge of the behavior of hundreds of applications. It's grueling work and it just flat out takes time–even for small applications.

- Cost Optimization - One of the beautiful things about cloud is an almost unlimited potential for cost savings. Take one person from your cloud team and task them with saving money at scale and they can come up with some mouth-watering numbers from doing seemingly simple things like shutdown schedules, instance right-sizing, RDS instance to Aurora migrations, EBS snapshot cleanup, etc. This sort of clutter piles up pretty quickly and a centralized team is well positioned to go after these targets. However, it's just flat out work and takes a lot of time to fix at scale.

- Asset Management - This is like keeping a rolling census on metadata that isn't easily standardized from a developer's perspective. For example, “If my application stores sensitive data do I put a tag on it that says

Data Classification: Highor do I putData Classification: high? Do I putdevordevelopment?” For more on why this is important see my ITSM and Cloud post. In any case, this can only really be done well by a central oversight team setting standards, writing governance automation, and regularly nagging people to put the right info down. - Architecture - The whole reason there's a central cloud team is because that's where the knowledge of the cloud platform lives. Sometimes developers have a rough idea of what the capabilities of the cloud are and can sketch something out on the back of a napkin but it's going to take someone who truly knows the hosting infrastructure to flesh out details such as routing tables, NACLs, Security Groups, available images, approved services, etc. Even if you have a great DevOps person on an app team they're not going to know all of the quirks of your hosting environment. Therefore, architectural support could range from a simple design review with minor suggestions to a full blown design/feature gathering engagement. Either way the central team will have to have some way of handling these requests.

- Build - It's very rare that central teams give every developer the permissions to build infrastructure. Even if they have

ec2:*permissions that's often not enough to do full builds when things like instance profiles are required. Some of this can be handled with permission boundaries, etc. but someone still has to maintain the guardrails and coach teams through things like Cloudformation tooling, tips and tricks for navigating SCP/Policy restrictions, etc. Depending on the service levels provided by the central team and the capabilities of the app teams these engagements could range from simple documentation to hands on keyboard build sessions. Either way there will have to be some sort of build liason. - Documentation - The smaller the team the more need there is for documentation. The whole point of the central team is to set standards, enforce policy, and provide general oversight. At the very least this should be a documentation portal that actually defines what the standards are. For example:

- Tagging Standards

- Identity Restrictions (e.g., “no IAM users allowed, roles only”)

- How To's for common questions

- Governance Restrictions on Services

The above responsibilities have almost unlimited variability in their broadness of scope dependent on company culture, team size, cyber security risk appetite, and application team skill levels. They could range from a simple documentation portal for a small central team to full service operations for a larger team. A lot of that has to do with whether or not the central team leans more towards custom work or standardized work.

Custom Work

Keep in mind that we've previously established that much of the power has been taken away from distributed application teams and the cloud is now governed by a centralized team. App teams are no longer able to do reckless things like peer VPC's with accounts outside the organization, create public IP's, have open S3 buckets, etc. If these are things that applications need in order to be successful then they are going to bump up against whatever controls are in place and will have to work closely with the central team.

With a “custom work” culture the projects will be complicated, time consuming, and engineers will be expensive. In order to maintain enough staff to cover the central team's responsibilities leadership will have to figure out a comprehensive funding model as their first order of business. This could simply be a per-application fee to manage custom cloud configurations which depending on how you do the math costs could be $10k/yr. It's undoubtedly a difficult conversation to go to an application team looking to host some Javascript and a lightweight PostgreSQL DB and tell them it will cost them $800/month for support for something that will likely never go down. But people often forget about all of the work that goes into even minor applications which are documented in the previous responsibilies section.

While most of this is standard regardless of the application size there are more challenges in managing larger applications which often have complex, multi technology architectures that require dedicated personnel when upgrades, patches, modifications need to be performed. Large applications are often important and draw a lot of attention during outages and will pull multiple engineers into bridges and post-mortems. However, these behemoths are also well funded meaning they can sustain higher maintenance fees.

For this reason it's likely that a “T-Shirt Size” approach can be used for maintenance fees from the central team when managing their application portfolio and could use a pricing and staffing model such as

| App Size | Monthly Fee | Number of Engineers |

|---|---|---|

| Small | $5k | 0.5 |

| Medium | $10k | 1 |

| Large | $20k | 2 |

These are pretty significant costs that would have to be passed back down to the app owners and likely down to their customers. This would ensure stable staffing and excellent service levels it's doubtful that many organizations can sustain a price structure like this. The costs could be shuffled a bit by requiring higher initial fees for roll out and smaller fees for maintenance but at the end of the day the engineer to application ratio still has to be maintained and funded in the custom architecture model.

What if we simply did not allow custom configurations at all? What if we were able to steer app teams towards standardized architecture? Would that allow us to still be effective? Would it make a difference in our cost structure?

Standardized Work

Let's assume the custom architecture model is too expensive and unsustainable and take a look at the second “standardization” approach. This would keep the per-application cost much lower and the range of technologies in use would shrink which presumably would make it easier to staff. Architectures would only be available in a few different flavors and therefore would be much easier to manage at scale which can push your required T-shirt funding model closer to something like:

| App Size | Monthly Fee | Number of Engineers |

|---|---|---|

| Small | $1k | 0.1 |

| Medium | $5k | 0.5 |

| Large | $10k | 1 |

But what would the trade-offs be?

Pros

- Cheaper labor.

- Self Service Architecture - Since the infrastructure is standard you could just put together a “Service Catalog” approach for compute and application teams could just pick everything from a drop down form. This would eliminate most of the need for a large architecture team. Everything that's available in this catalog could have patching agents, security hardening, monitoring baked into the images and bootstrap scripts. This approach is nothing new and was pretty common even back in the early days of VMWare. The drawbacks of course are that people will have over allocated infrastructure and will likely leave unused capacity laying around everywhere but if you have your billing system optimized it could mostly self-police.

- Ease of Maintenance - Standardized work would be far easier to maintain in the long run. Patching and upgrades become routine and scalable. Monitoring and log collection can be standardized.

- Economies of Scale - Vendor licensing can be purchased in bulk. Reserved Instances/Spending Plans can be created with relative ease. Cheaper instance types can be pushed out in massive waves.

- Simplicity of operations. People often underestimate the amount of work that goes into handling edge cases when new technologies are allowed. For the people doing the work it means a lot more work and for the managers it means more sleepless nights.

Cons

- Inflexible architecture will cause large inefficiencies from app to app.

- Innovation will suffer and people looking to do interesting things will get lost in the bureaucracy.

- Abuse would increase as people would start getting very creative within their walled gardens and start doing things like overloading servers with multiple apps.

- Higher cloud vendor bill due to inefficiencies even though labor costs go down.

- Attracting and retaining talent would be difficult because “cloud people” don't like boring work.

While there are many benefits to a rigid standardized model is likely not sufficient for many organizations due to its inelasticity. There will always be some special app that comes along that will end up having high visibility from leadership and get shoved through the team. These will just end up being asterisks and exceptions that will be cause stress for everyone. For that reason we want to have a “happy path” for more complex work as well.

What if we were to take the two approaches and blend them together?

Hybrid Approach

We want to have a fast track for standard applications and also be able to support more complex applications. The way we would do this in any free market system is to make the standard path really cheap and make the custom path expensive. If we had a mix of capabilities on our price sheet then in a perfect world it might look like this:

| App Category | Monthly Fee | Number of Engineers |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Small | $1k | 0.1 |

| Standard Medium | $5k | 0.2 |

| Standard Large | $10k | 0.5 |

| Custom Small | $12k | 0.8 |

| Custom Medium | $20k | 1 |

| Custom Large | $30k | 2 |

This would give us categories in which to place our existing, fully custom applications but also provide lower cost, easier to manage catgory for standardization. It also gives us a goal–start filling the Standard buckets with net new applications and look to refactor older applications. Let's assume this is a fairly sane model that we want to try to put into practice. For that, let's look at a real world centralized cloud hosting organization that's struggling and see if we can make it work.

Case Study

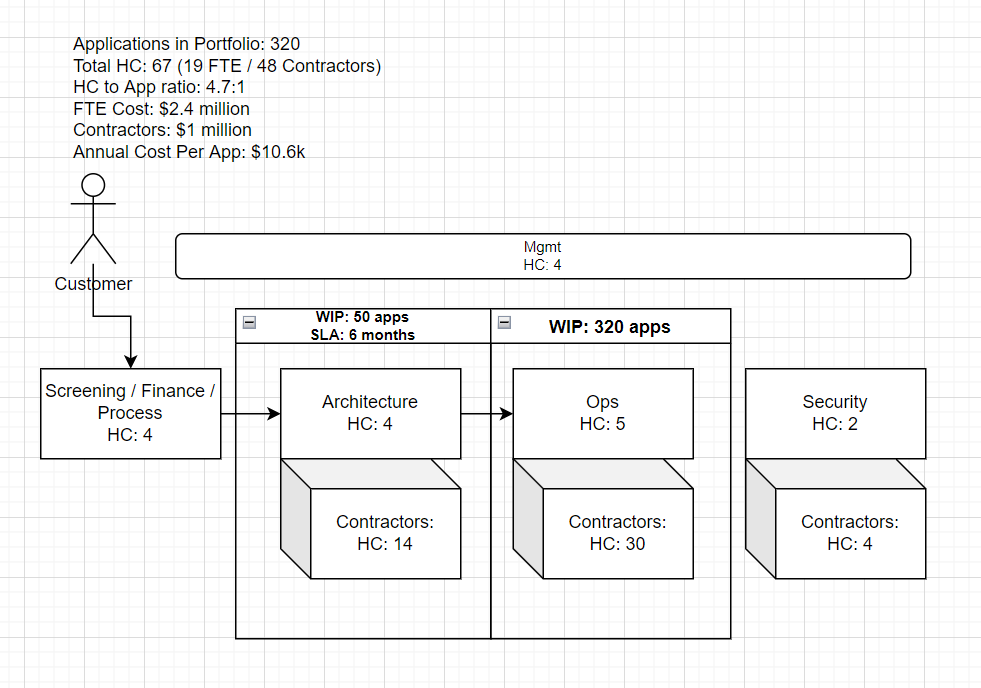

The above diagram describes a team that controls access to their cloud environments and the apps that go into them. The team feels are severely understaffed for the number of applications in their portfolio. When requests come in for very simple changes (e.g., add a new load balancer so a site is internet facing) it can take up to 6 months to service the request. This is because larger, more important projects are taking up all of the resources on the team. This could be solved somewhat by better time management but it's really a simple case of every application needing custom infrastructure, no patterns for standard infrastructure, and then also being understaffed. Let's say the team convinces their leadership that they need to hire more engineers but the question is “how many more do we need?".

Let's assume that middle management takes the advice of this article and does some math. They find out which of the applications in their portfolio fall into the T-Shirt categories and publish the findings. They also apply some additional calculations to determine actual costs.

Assuming per engineer (FTE and contractor) average salary of 100k USD

| App Category | Monthly Fee | Break Even Fee | Number of Engineers | Number of Applications | Required Engineers | App2Eng Ratio | Annual Cost | Annual Revenue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Small | $800 | $833 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.2 | 10 | $20,000 | $19,200 |

| Standard Medium | $1,600 | $1,667 | 0.2 | 5 | 1 | 5 | $100,000 | $96,000 |

| Standard Large | $3,000 | $3,333 | 0.4 | 10 | 4 | 2.5 | $400,000 | $360,000 |

| Custom Small | $6,000 | $6,667 | 0.8 | 200 | 160 | 1.25 | $16,000,000 | $14,400,000 |

| Custom Medium | $8,000 | $8,333 | 1 | 100 | 100 | 1 | $10,000,000 | $9,600,000 |

| Custom Large | $12,000 | $13,333 | 1.6 | 3 | 4.8 | 0.625 | $480,000 | $432,000 |

| TOTAL | 320 | 270 | 1.875 | $27,000,000 | $24,907,200 |

When management gets together and looks at the size of the current organization and the requirements per the model they are shocked. Based on this model they are almost 200 employees short of meeting the requirements. While this certainly reflects what the engineers are feeling on the ground it probably doesn't make economic sense to add 200 heads. More than likely they are not adequately billing their customers to support such an adjustment. What can be done about this? Well, first of all we could try to charge more for our services. This would be a big political negotiation between them and their stakeholders that probably won't go well. While they're selling that they can try to fit applications into more standardized models that are more economical. Let's pretend for a moment that some analysis is done and a few hundred applications are recategorized as being candidates for the Standard category.

| App Category | Monthly Fee | Break Even Fee | Number of Engineers | Number of Applications | Required Engineers | App2Eng Ratio | Annual Cost | Annual Revenue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Medium | $1,600 | $1,667 | 0.2 | 80 | 16 | 5 | $1,600,000 | $1,536,000 |

| Standard Large | $3,000 | $3,333 | 0.4 | 15 | 6 | 2.5 | $600,000 | $540,000 |

| Custom Small | $6,000 | $6,667 | 0.8 | 12 | 9.6 | 1.25 | $960,000 | $864,000 |

| Custom Medium | $8,000 | $8,333 | 1 | 8 | 8 | 1 | $800,000 | $768,000 |

| Custom Large | $12,000 | $13,333 | 1.6 | 5 | 8 | 0.625 | $800,000 | $720,000 |

| SUBTOTAL | 320 | 67.6 | 1.875 | $6,760,000 | $6,348,000 |

Now everyone gets excited. The current headcount matches what's required almost exactly! Now all we have to do is get our billing sorted out and we can start bringing in revenue for this department. High fives all around. However, the grizzled ops manager raises their hand and bursts everyone's bubble by saying “Yeah, the only problem is that someone needs to actively refactor all those applications and this organization is dysfunctional. It takes 6 months to get anything done and I have to chew on garbage all day because there's no consistency”. Why is that? What are we doing wrong?

One of the reasons that we've already considered is that all of the applications are in currently under the Custom category and it would be a large effort to standardize the existing portfolio. Maybe we'd have enough headcount if we'd started keeping apps in their lanes from day one but we'll have to agree that at the very least, from this day forward, all new apps must correctly fall into one of the product categories. The type of organizational transformation that would need to take place to refactor all existing apps monumental and is outside of the scope of this discussion.

However, for kicks, let's assume that all the apps magically transformed in to easy-to-manage standard infrastructure. Would we be in good shape? Possibly, but there's another aspect of this example team that we haven't covered yet that will threaten its success–yes, it's that elephant in the room you may have noticed in the org chart–the Contractors.

How To Fix The Organization

Here we will present a bold statement: Even if our hypothetical organization had all of the apps refactored into their correct categories they would still be dysfunctional because of the ratio of employees to contractors on the team and the lack of any surplus headcount for fixing technical debt. This isn't necessarily because the individuals on the team don't care, it's because there is so much to care for that the caring wears thin. Why is caring important?

When people don't care about what they're working on then everything else fails–the designs lack thought, the operations aren't stable, they're unmotivated and speed to market suffers. We're talking about very complex systems being worked on by highly educated and seasoned professionals. It's not that the employees and contractors are incapable of caring, it's just that employees have too much to care about and contractors aren't empowered or paid to care so they can't shoulder any of the burden.

These complex sytems are not much different than large codebases in that they have inter-dependencies and edge cases. Just like developers working on a shared codebase, it's very difficult to transfer the train of thought for a new feature to another person at the end of a shift–once an engineer has a system loaded into their brain it makes the most sense to have that engineer own and finish the job. Therefore, one of the most important factors in an organization that manages complex things is a culture of ownership. Let us quickly define what we mean by ownership in this context of cloud based application's infrastructure. An engineer must:

- Understand what the app does.

- Understand who the stakeholders are.

- Understand the basic architecture is.

- Understand how much downtime the app can handle and what its weaknesses are.

- Understand how to make changes to the app infrastructure.

- Understand how to monitor the performance of the application

- Understand how much the app's infrastructure costs the stakeholders

Somebody has to know all of these things to adequately support the application! Our example team appears to have enough good people, they're highly paid and they didn't get to this point in life without caring about technology. So why then are good people failing to take ownership? Let's examine some possible factors:

- They are contractors who don't have clear requirements and are paid to execute, not own.

- The organization is all toil and has no moon-shots or heroic teams working to someday fix the problems in the work.

- They are understaffed, overworked, jaded and burnt out

- Their customers don't give a damn so why should they?

First of all, contractors are good people. They are often highly technical, amiable, and hard working. Of course, this varies based on their rates but generally holds true. The biggest problem is that no matter how expensive they are they will never be able to provide the level of ownership by themselves that is required to support a complex application. It's just a fundamental rule embedded in the nature of the relationship. They are paid to execute tasks and even if they are given the task of ownership they will always fall short of what is needed for an organization because the nature of the relationship is temporary. They will not be given the same tools as employees and everyone they interact with inside the organization knows that there is an egg timer ticking and they will fail to create lasting relationships. Even if contractor tenureship is longer than the full time employees due to attrition it's still a scarlet letter stamped on them in the company directory. It's just human nature. With that being said though, how can we plan for this? Well, an attempt has been made to do just that by using the ownership formula but it's more art than science. However, we'll use this formula in our new team model later after we cover the other factors.

To address the second barrier to ownership, if the organization is all toil and there are no “moon-shots” it means that the people on the team see no hope for the future. Even if all of their work is going well then human psychology will still make them only see the annoying parts of their job. If they know that there is nobody working on making “the workplace of tomorrow” then all hope is lost. People need to be able to think about an unsolvable problem in their daily life and think to themselves “After person builds thing maybe this will get better, I'll just keep toiling for now because I know there is some hope”. We'll have to factor this into our design of a highly functional team.

The overworked problem should hopefully work itself out once the team is staffed appropriately per our model. Staffing up the aforementioned moon-shot team should give a temporary morale boost in the mean time.

For the last bullet, what if the customers we're serving don't seem to care whether or not the designs are good and the infrastructure is stable? This is actually a very common problem in large organizations where apps have been moved around and inherited as departments restructure and employees leave. It's demoralizing to work for hours on a design or a fix and proudly present your findings to a room full of crickets. This is where management and culture has to step in and save the day. Jeff Bezos once said in a shareholder letter that “High standards are contagious”. Observations of real world teams indicate that as long as there is one person–be it a customer, manager, or peer that seems to care about the quality of your work then that is often enough to replace the lack of care from a customer. This will come in time as the entire organization's level of quality and pride go up.

So to recap how we're going to modify the model: we're going to talk about ownership requirements instead of raw headcount and we're going to add some additional capaciy for toil/moon-shot. We're hoping that the understaffed and customer care factor will eliminate itself over time. With that, let's see how our model looks now:

| App Category | Monthly Fee | Break Even Fee | Own Required per App | Number of Applications | Required Own | App2Own Ratio | Annual Cost | Annual Revenue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Small | $800 | $711 | 0.1 | 200 | 20 | 10 | $1,706,700 | $1,920,000 |

| Standard Medium | $1,600 | $1,422 | 0.2 | 80 | 16 | 5 | $1,365,360 | $1,536,000 |

| Standard Large | $3,000 | $2,845 | 0.4 | 15 | 6 | 2.5 | $512,010 | $540,000 |

| Custom Small | $6,000 | $5,689 | 0.8 | 12 | 9.6 | 1.25 | $819,216 | $864,000 |

| Custom Medium | $8,000 | $7,111 | 1 | 8 | 8 | 1 | $682,680 | $768,000 |

| Custom Large | $12,000 | $11,378 | 1.6 | 5 | 8 | 0.625 | $682,680 | $720,000 |

| SUBTOTAL | 320 | 67.6 | 1.875 | $5,768,646 | $6,348,000 | |||

| Toil/Moonshot adder [5%] | ||||||||

| TOTAL | 70.98 | |||||||

| Avg Cost Per Own | $85,335 | |||||||

| Contractor Cost | $60,000 | |||||||

| Employee Cost | $100,000 |

Therefore, the target ownership size to manage these 320 applications long term is somewhere around 71 if everything has been properly sorted into the Standard and Custom categories. Which based on the ownership formula is optimally achieved by a team of 45 FTE's and 25 contractors. This really isn't that bad. Of course, getting the portfolio to fit into this model will take substantially more resources but at least we can see some light at the end of the tunnel.

Obviously, the level of ownership required for each app in each category may need to be tweaked based on your own workloads. Also, for quality improvements you can just raise contractor and FTE salaries. While this was just an example of a single organization it likely applies to many teams. What can we learn from this exercise?

Conclusion

The bottom line is that cloud infrastructure is just damned complicated these days. It's very difficult to divorce the application from the infrastructure and thus the application to engineer ratio has gotten lower and lower as the list of cloud features has grown. As a result of this complexity, more and more engineers are needed to manage cloud infrastructure. The need for centralized security oversight along with the scarcity of cloud talent is driving organizations to set up centralized teams that claim to fully manage cloud infrastructure.

We have entered an era in enterprise cloud where most of us need to be driving our applications to work in Honda Civics and Ferrari's should be expensive to drive. In other words, standardized work should be the easy way to get applications hosted with few barriers. Custom architecture should be available albeit expensive. Either way, the most important aspect is having a rock solid funding model for both approaches which is likely higher than most people expect.

Furthermore, if you're looking at how to fix an existing team that is operating fully custom portfolios, you're going to have to have massive headcount increases until app infrastructure can be standardized. The only way out of this mess is to hire lots and lots of engineers to get the portfolios under control with the express goal of forcing everything into standard models so that one day, the total size of the team can be eventually reduced. However, the good news is that we can staff these teams with contractors to reduce the costs as long as we stick to the 5:4 FTE/Contractor ratio.

So, assuming centralized cloud teams aren't going away anytime soon as they aren't going to be saying “no” to any of the work coming their way the only solution out of this mess is:

- Start charging higher fees for managing the applications.

- With the higher fees and as much additional money as possible, hire a lot more engineers.

- Start forcing standard infrastructure so you don't have to expand the team exponentially moving forward.

Thank you for taking the time to read this analysis. Hopefully it reflects your experiences in the real world and gives you some food for thought when planning for centralized cloud team structure and headcount.

Costs Appendix

Click to expand

What we mean by "expensive" may need some qualification. A typical enterprise has a portfolio of at least a few hundred applications that require some sort of hosting infrastructure. Frequently, these workloads are being pushed to cloud for a litany of reasons that are outside the scope of this post. In order to design, build, secure, operate, and monitor each application it requires certain skill sets which are broken down by the following table based on their market rates and timeshare for how long their skills are required. Not every organization has their teams structured like this as sometimes all the roles are being performed by a more or less persons however, it is representative of a typical enterprise team leaning more towards the "Custom Work" model for a small application with a few external integration requirements (e.g., connection to an on-prem database).Costs are in USD for mid-level U.S. based engineers.

| Role | Task | Salary | Time Required | One Time Cost | Ongoing Cost (annually) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solutions Architect | Design | $128k [1] | 3 weeks^ | $5k | $2.5k |

| Ops Engineer | Build/Run | $100k | 3 weeks^^ | $3.8k | $1.2k |

| Security | Review/Monitor | $120k | 1 week^^^ | $1k | $1k |

| TOTAL | $9.8k/app | $4.7k/app |

^ The architect gathers requirements from stakeholders, puts together drawings, prepares firewall requests, plans timelines, etc. Their time is usually spread across multiple projects which for a small application can equate to about two total weeks of focus time. You can also expect some feature enhancement, refactor, or other kind of follow up work in the near future which is covered by the Ongoing Cost estimate.

^^ The Ops Engineer builds the environment per spec from the architect and invariably has to make tweaks along the way based on reality which take up time. Also, they can expect to have ongoing time commitments due to outages, patching, etc. Initial build/deploy time can easily take a week and a few outages or patch windows can consume the remaining two weeks.

^^^ The security team can be expected to sign off on any designs, validating the use of new technologies, pushing back on requests, etc. which can take a few meetings per application. There are typically expected to build monitoring infrastructure to validate security requirements on a continuous basis such as vulnerability scanning, liberal use of ports, key rotations, etc.)

While most of these numbers fairly represent small to medium sized applications they can vary greatly depending on the complexity of the application, how many integrations with other applications are required, the organization's maturity with the technologies requested in the architecture, etc. However, for the purposes of this demonstration let's just pretend this is an accurate average cost. So looking at this hypothetical three person team you can work out some macro statistics.

- Cost and Throughput of a 3-Engineer Cloud Team

- Maximum Throughput (new projects annually) = 17 apps

- Annual Cost (new projects) = $166k

- Annual Maintenance (for 17 apps) = $80k/yr

Reference

- [1] - Cloud Solutions Architect Salary - (https://www.payscale.com/research/US/Job=Cloud_Solutions_Architect/Salary)